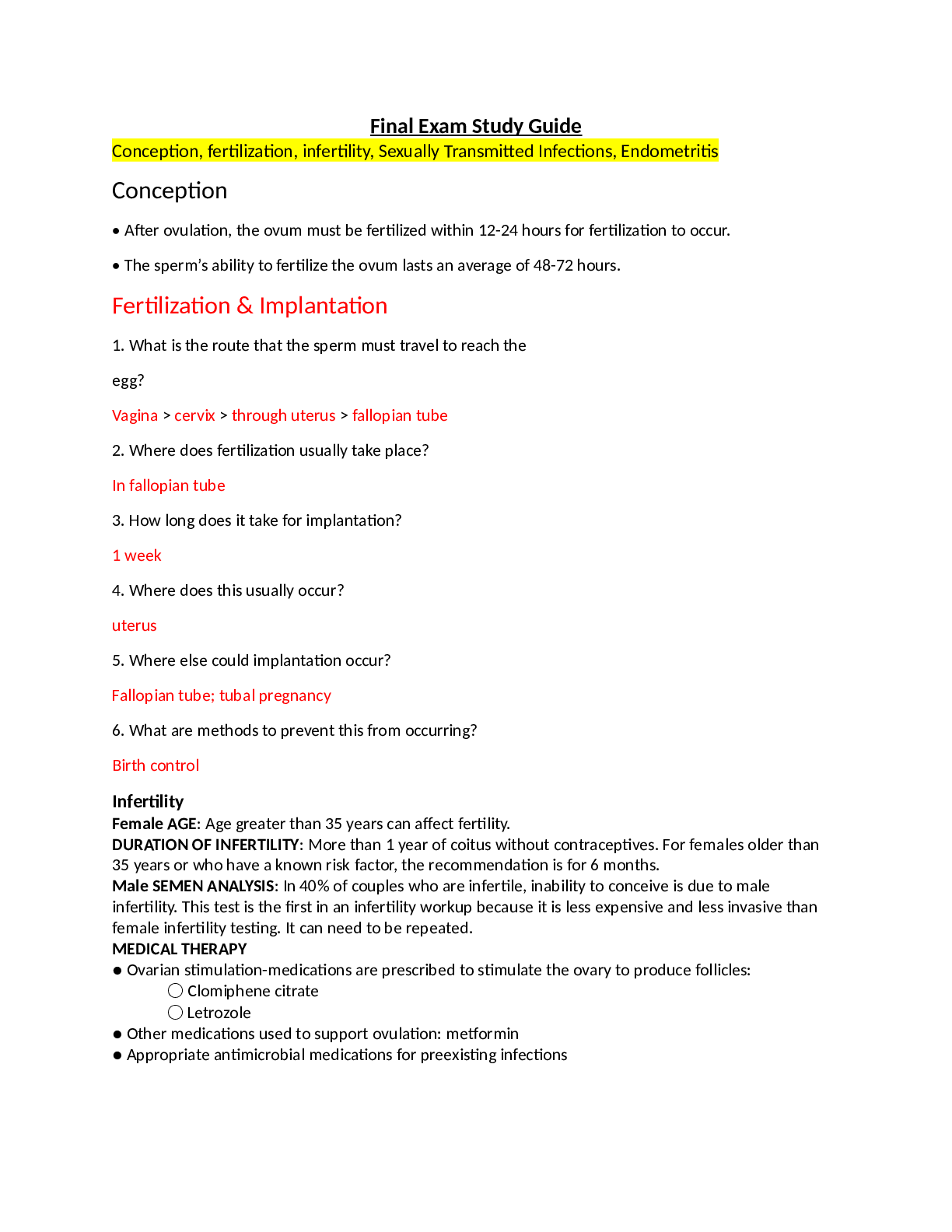

Signs of pregnancy

presumptive (subjective signs) Amenorrhea, nausea, vomiting, increased urinary frequency,

excessive fatigue, breast tenderness, quickening at 18–20 weeks

probable (objective signs) Goodell sign (sof

...

Signs of pregnancy

presumptive (subjective signs) Amenorrhea, nausea, vomiting, increased urinary frequency,

excessive fatigue, breast tenderness, quickening at 18–20 weeks

probable (objective signs) Goodell sign (softening of cervix)

Chadwick sign (cervix is blue/purple)

Hegar’s sign (softening of lower uterine segment)

Uterine enlargement

Braxton Hicks contractions (may be palpated by 28 weeks)

Uterine soufflé (soft blowing sound due to blood pulsating through the placenta)

Integumentary pigment changes

Ballottement, fetal outline definable, positive pregnancy test (could be hydatidiform mole,

choriocarcinoma, increased pituitary gonadotropins at menopause)

positive (diagnostic signs) Fetal heart rate auscultated by fetoscope at 17–20 weeks or by Doppler at

10–12 weeks

Palpable fetal outline and fetal movement after 20 weeks

Visualization of fetus with cardiac activity by ultrasound (fetal parts visible by 8 weeks)

Pregnancy and fundal height measurement

Signs of pregnancy (presumptive, probable, positive)

Pregnancy and fundal height measurement As pregnancy progresses, the

fundus rises out of the pelvis (Figure 29-1). At 12 weeks’ gestation, the fundus is

located at the level of the symphysis pubis. By week 16, it rises to midway between

symphysis pubis and the umbilicus. By 20 weeks’ gestation, the fundus is typically at the

same height as the umbilicus. Until term, the fundus enlarges approximately 1 cm per

week. As the time for birth approaches, the fundal height drops slightly. This process,

which is commonly called lightening, occurs for a woman who is a primigravida around

38 weeks’ gestation but may not occur for the woman who is a multigravida until she

goes into labor

Naegele’s rule

Add seven days to the first day of your LMP and then subtract three months. For

example, if your LMP was November 1, 2017: Add seven days (November 8, 2017).

Subtract three months (August 8, 2017).

The EDD is calculated by adding seven days to the first day of the last menstrual period, subtracting

three months and adding one year.

This formula is known as Naegele's Rule. For example, if the patient's last menstrual period, LMP,

was on August 10, 2019, the EDD would be calculated as follows. LMP equals August 10, 2019 plus

seven days. August 17, 2019, minus three months. May 17, 2019 plus one year and that equals May

17, 2020.

Hematological changes during pregnancy

During pregnancy, the heart is displaced upward and to the left within the chest cavity

by the gravid uterus’s pressure on the diaphragm. As pregnancy progresses, the risk for

inferior vena cava and aortic compression leading to supine hypotension increases

when the woman lies in a supine position. To avoid hypotension and potential syncope,

the woman should be advised to lie in a left lateral position. Hemodynamic changes and

anatomic changes also may alter vital signs in the pregnant woman (Table 29-2).

Cardiac output in pregnancy increases by 30% to 50% over that in women who are not

pregnant (Blackburn, 2013; Ouziunian & Elkayam, 2012). This increase

peaks in the early third trimester and is maintained until birth. Half of the total increase

in cardiac output, however, occurs by the eighth week of pregnancy (Blackburn,

2013). Therefore, women with cardiac disease may become symptomatic during the

first trimester. Stroke volume is also increased during pregnancy by 20% to 30%. These

increases in cardiac output and stroke volume allow for the 30% increase in oxygen

consumption observed during pregnancy.

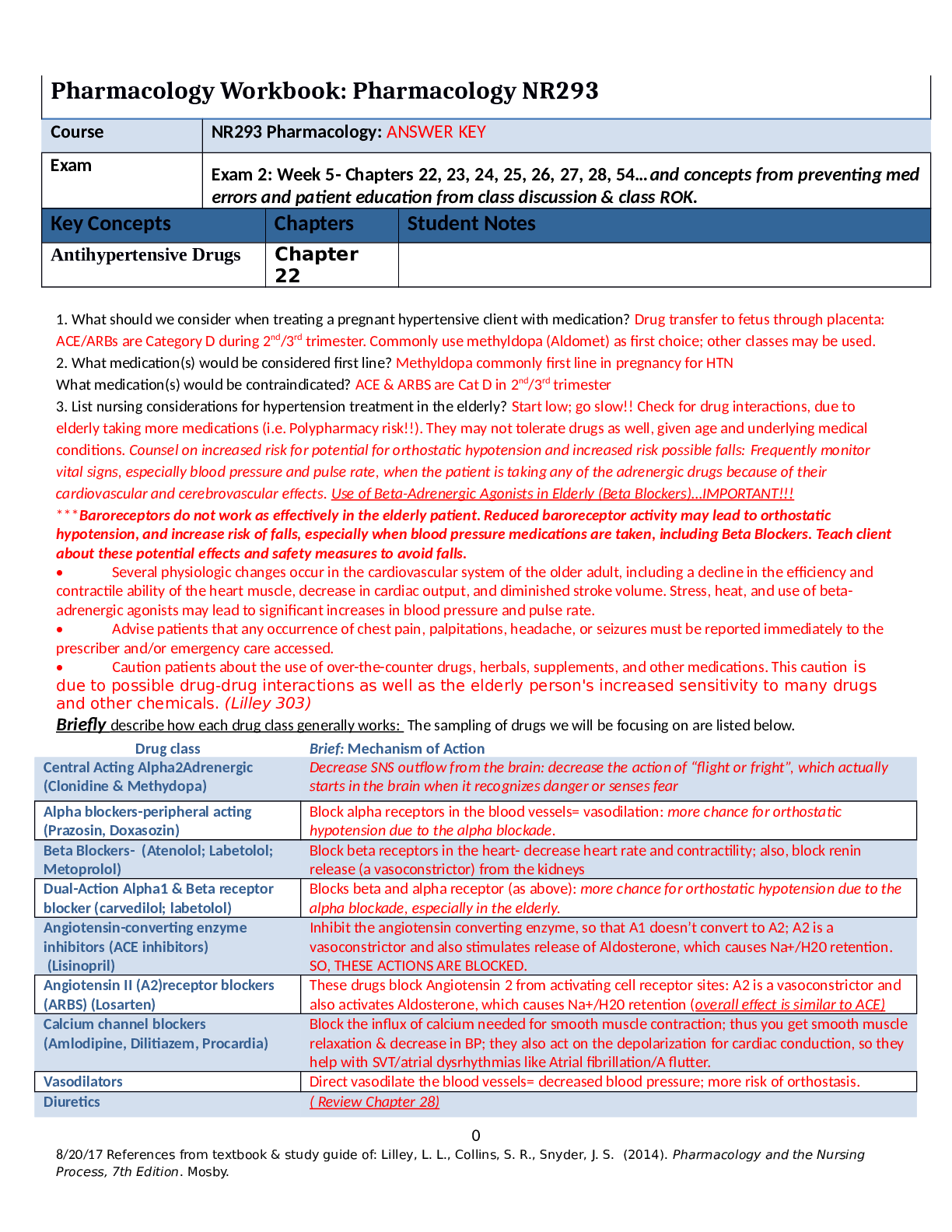

TABLE 29-2 Vital Sign Changes in Pregnancy

Vital Sign Changes in Pregnancy Measurement Alterations in

Pregnancy

Heart rate

and heart

sounds

Volume of the first heart sound

may be increased with splitting.

Third heart sound may be

detected.

Systolic murmurs may be detected.

Increases by 15–20 beats/min by

32 weeks’ gestation.

Palpate the maternal pulse when

auscultating the fetal heart rate to

be able to distinguish between the

two.

Respiratory

rate

Increases by 1–2 breaths/min None

BP First trimester: same as

prepregnancy values

Second trimester: systolic BP

decreases by 2–8 mm Hg and

diastolic BP decreases by 5–15 mm

Hg due to peripheral vascular

resistance

Third trimester: gradually returns to

prepregnancy values

Use of an automated cuff may

improve accuracy of

measurement, as some pregnant

women do not have a fifth

Korotkoff sound.

Systolic and diastolic BP may be

16 mm Hg higher when taken

while the woman is sitting.

BP readings may decrease in the

maternal left lateral position.

Abbreviation: BP, blood pressure.

Data from Jarvis, C. (2016). Physical examination and health assessment (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO:

Saunders Elsevier; Ouziunian, J., & Elkayam, U. (2012). Physiologic changes during normal

pregnancy and delivery. Cardiology Clinics, 30, 317–329; Tan, E., & Tan, E. (2013). Alterations in

physiology and anatomy during pregnancy. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics &

Gynaecology, 27, 791–802.

During pregnancy, blood volume increases by 30% to 50%, or 1,100 to 1,600 mL

(Ouziunian & Elkayam, 2012), and peaks at 30 to 34 weeks’ gestation. The

increase in blood volume improves blood flow to the vital organs and protects against

excessive blood loss during birth. Fetal growth during pregnancy and newborn weight

are correlated with the degree of blood volume expansion.

Of the blood volume expansion occurring during pregnancy, 75% is considered to be

plasma (King et al., 2015). There is also a slight increase in red blood cell volume

(RBC). The blood volume changes result in hemodilution, which leads to a state of

physiologic anemia during pregnancy. As the RBC volume increases, iron demands also

increase. Leukocytosis occurs in pregnancy, with white blood cell counts increasing to

as much as 14,000 to 17,000 cells per mm3 of blood (Table 29-3). Clotting factors

increase as well, creating a risk for clotting events during pregnancy.

Systemic vascular resistance is reduced due to the effects of progesterone,

prostaglandins, estrogen, and prolactin. This lowered systemic vascular resistance, in

combination with inferior vena cava compression, is partly responsible for the

dependent edema that occurs in pregnancy. Epulis of pregnancy, or hypertrophy of the

gums accompanied by bleeding, may also occur and is due to decreased vascular

resistance and increase in the growth of capillaries during pregnancy (Jarvis, 2016).

Indications and contraindications for prescribing combined estrogen

vs. progesterone-only birth control

Progestin-only contraceptives are used continuously; there is no hormone-free interval,

as occurs with combined methods. These contraceptive methods have minimal effects

on coagulation factors, blood pressure, or lipid levels and are generally considered safer

for women who have contraindications to estrogen, such as cardiovascular risk factors,

migraine with aura, or a history of VTE. In spite of this belief, the product labeling for

some progestin-only products mimics the labeling for products containing estrogen.

The U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (CDC, 2010;

see Appendix 11-A) can be used to identify appropriate candidates for progestinonly contraception.

Progestin-only contraceptives do not provide the same cycle control as methods

containing estrogen, and unscheduled bleeding is common with all progestin-only

methods. Typically, unscheduled bleeding occurs most frequently during the first 6

months of method use, with a substantial number of users becoming amenorrheic by 12

months of use (Hubacher, Lopez, Steiner, & Dorflinger, 2009). Overall blood

loss decreases over time, making progestin-only methods protective against irondeficiency anemia. With appropriate counseling, many women see amenorrhea as a

benefit of these methods.

All progestin-only methods are likely to improve menstrual symptoms, including

dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, premenstrual syndrome, and anemia (Burke, 2011).

The thickening of cervical mucus seen with progestin methods is protective against PID.

Progestin-only contraceptives include the progestin-only pill (POP), an injection, an

implant, and three progestin-containing intrauterine devices. The implant and devices

are covered in the section on long-acting reversible contraception.

The U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (CDC, 2010) is a

comprehensive, evidence-based guide for determining whether women have relative or

absolute contraindications to contraceptive methods. The Medical Eligibility

Criteria uses the following four classification categories of whether a person can use or

should not use a method:

Category 1: a condition for which there is no restriction for the use of the

contraceptive method

Category 2: a condition where the advantages of using the method generally

outweigh the theoretical or proven risks

Category 3: a condition where the theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh

the advantages of using the method

Category 4: a condition that represents an unacceptable health risk if the

contraceptive method is used

Menstrual cycle physiology

The initiation of menstruation, called menarche, usually happens between the ages of

12 and 15. Menstrual cycles typically continue to age 45 to 55, when menopause

occurs. Many women find themselves reluctant to discuss the existence and normality

of menstruation. The word menstruation has been replaced by a variety of euphemisms,

such as the curse, my period, my monthly, my friend, the red flag, or on the rag.

Most women experience deviations from the average menstrual cycle during their

reproductive years. As a result, it is not uncommon for women to display certain

preoccupations regarding their menstrual bleeding, not only in relation to the regularity

of its occurrence, but also in regard to the characteristics of the flow, such as volume,

duration, and associated signs and symptoms. Unfortunately, society has encouraged

the notion that a woman’s normalcy is based on her ability to bear children. This

misperception has understandably forced women to worry over the most miniscule

changes in their menstrual cycles. Indeed, changes in menstruation are one of the most

frequent reasons why women visit their clinician.

Numerous patterns in the secretion of estrogens and progesterone are possible; in fact,

it is difficult to find two cycles that are exactly the same. Studies that include women of

different ethnicities, occupations, genetics, nutritional status, and age have

demonstrated that the length and duration of the menstrual cycle vary widely (Assadi,

2013; Johnson et al., 2013; Karapanou & Papadimitriou, 2010).

Menarche is the most readily evident external event that indicates the end of one

developmental stage and the beginning of a new one. It is now believed that body

composition is critically important in determining the onset of puberty and menstruation

in young women (Ferin & Lobo, 2012). The ratio of total body weight to lean body

weight is probably the most relevant factor, and individuals who are moderately obese

(i.e., 20–30% above their ideal body weight) tend to have an earlier onset of menarche

(Johnson et al., 2013). Widely accepted standards for distinguishing what are

regular versus irregular menses, or normal versus abnormal menses, are generally

based on what is considered average and not necessarily typical for every woman.

According to these standards, the normal menstrual cycle is 21 to 35 days with a

menstrual flow lasting 4 to 6 days, although a flow for as few as 2 days or as many as 8

days is still considered normal (Ferin & Lobo, 2012).

The amount of menstrual flow varies, with the average being 50 mL; nevertheless, this

volume may be as little as 20 mL or as much as 80 mL. Generally, women are not

aware that anovulatory cycles and abnormal uterine bleeding (changes in bleeding

outside of normal; see Chapter 24) are common after menarche and just prior to

menopause (Ferin & Lobo, 2012; Fritz & Speroff, 2011). Menstrual cycles

that occur during the first 1 to 1.5 years after menarche are frequently irregular due to

the immaturity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis (Fritz & Speroff, 2011).

Vaccines during pregnancy

Live vaccines are contraindicated during pregnancy (MMR, Oral Polio, Varicella

& FluMist)

Injectable influenza vaccine is an inactivated virus and is safe to use in

pregnancy

Ask if the woman has ever known anyone with tuberculosis or traveled to areas where

tuberculosis is common. If she is at risk, she should receive a tuberculin skin test when

she can return in 48 to 72 hours. Past history of varicella is important, as well as the

woman’s vaccine history, to determine if she is at risk for chickenpox.

Women can receive vaccines in pregnancy (Table 30-1). The Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC) updates the adult vaccine schedule often, and this

information can be easily accessed on its website. The CDC website also includes

detailed information about safety of vaccines for travel of local disease outbreaks during

pregnancy (CDC, 2014). All women who are pregnant should be offered the influenza

vaccine during flu season, though live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV [FluMist])

should not be given to pregnant women. All women should be encouraged to receive a

tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccination in the third trimester

(CDC, 2016). Other vaccines, such as hepatitis B, can be administered if the woman

is at risk (CDC, 2016).

During pregnancy, women have a decreased immune response to pathogens, making

them more susceptible to infection. If a woman has cats, she should be careful to avoid

contracting toxoplasmosis—an infection that is spread through cat feces. Someone else

should change the cat litter box daily to prevent contact with the Toxoplasma

gondii parasite. Wearing gloves while gardening, and careful hand washing are also

essential. More information and patient handouts are available for free at the CDC

website.

TABLE 30-1 Vaccines in Pregnancy

Recommended Each Preg

nancy

Rationale Timing

Influenza (flu)a Women who are pregnant are at

increased risk for flu-related

complications.

Any

gestation

when the

injection is

available

[Show More]