Virtual Lab: Projectile Motion

Name(s):

Date:

Please use a font color other than black, red or green.

Theory:

A projectile is an object that moves in two dimensions, in other words, it moves vertically

and horizont

...

Virtual Lab: Projectile Motion

Name(s):

Date:

Please use a font color other than black, red or green.

Theory:

A projectile is an object that moves in two dimensions, in other words, it moves vertically

and horizontally at the same time. A special characteristic of a projectile is that its

motion in the vertical direction is independent of its motion in the horizontal direction.

If air resistance is small enough to be ignored, then the only force acting on a projectile

after launch, is the vertical force of gravity. Therefore, in the absence of air resistance,

the horizontal component of the projectile’s velocity does not change. In the vertical

direction, the force of gravity causes a constant downwards acceleration of 9.8 m/s2.

The projectile’s motion in the vertical direction can therefore be analyzed using

kinematic equations that are based on constant acceleration such as:

y=y0+v0 yt−

12

g t2[Equation1]

where:

y = change in height of the projectile (in meters)

y0 = initial height of the projectile (before it was launched)

voy = initial velocity of the projectile in the vertical direction

g = acceleration due to gravity (9.8 m/s2). We put a negative sign in front of g to indicate

that we have chosen upwards as the positive direction, and g is directed downwards.

t = time in seconds since the launch of the projectile

Projectile motion is seen when you throw a ball across to someone, when you hit a

baseball or a tennis ball, when water emerges out of a fountain and so on.

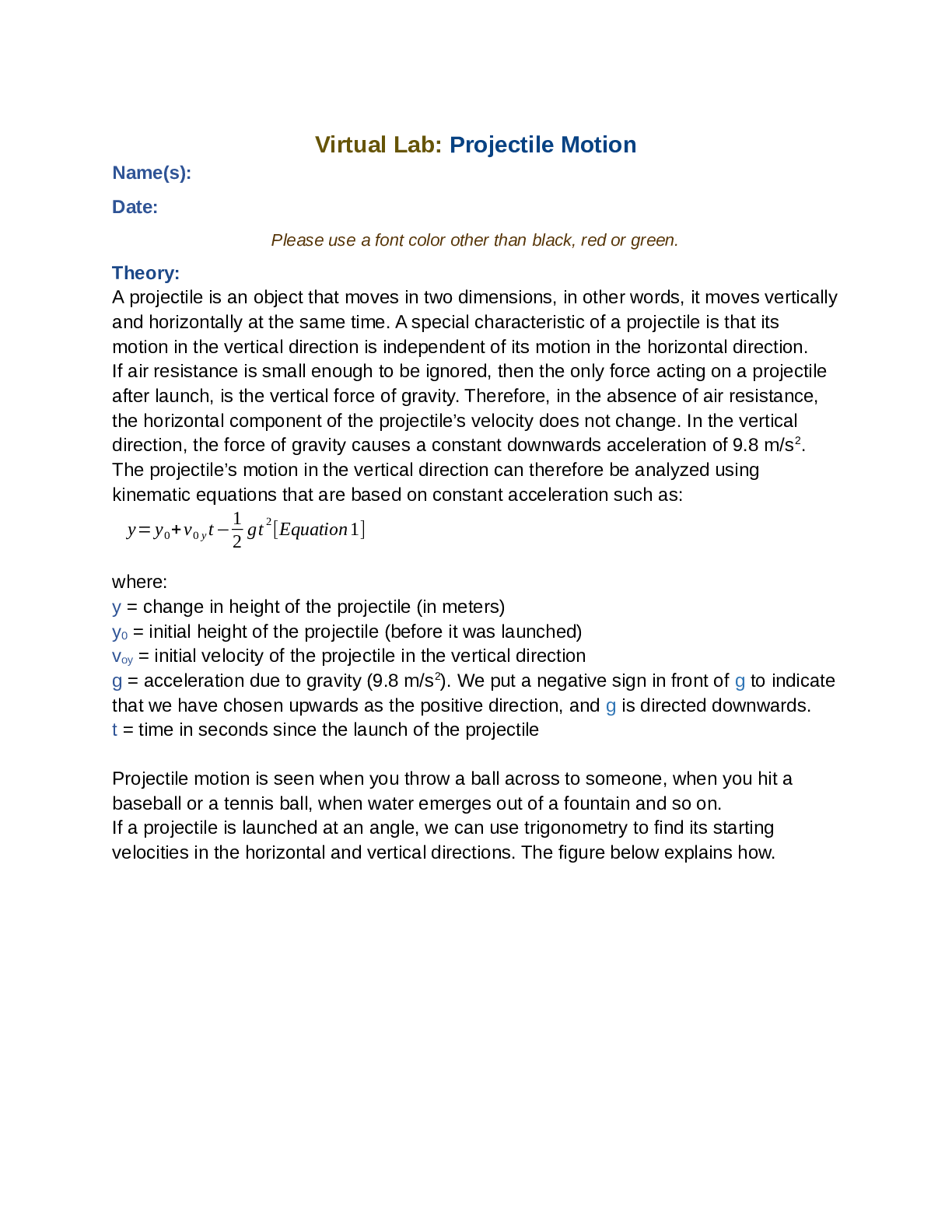

If a projectile is launched at an angle, we can use trigonometry to find its starting

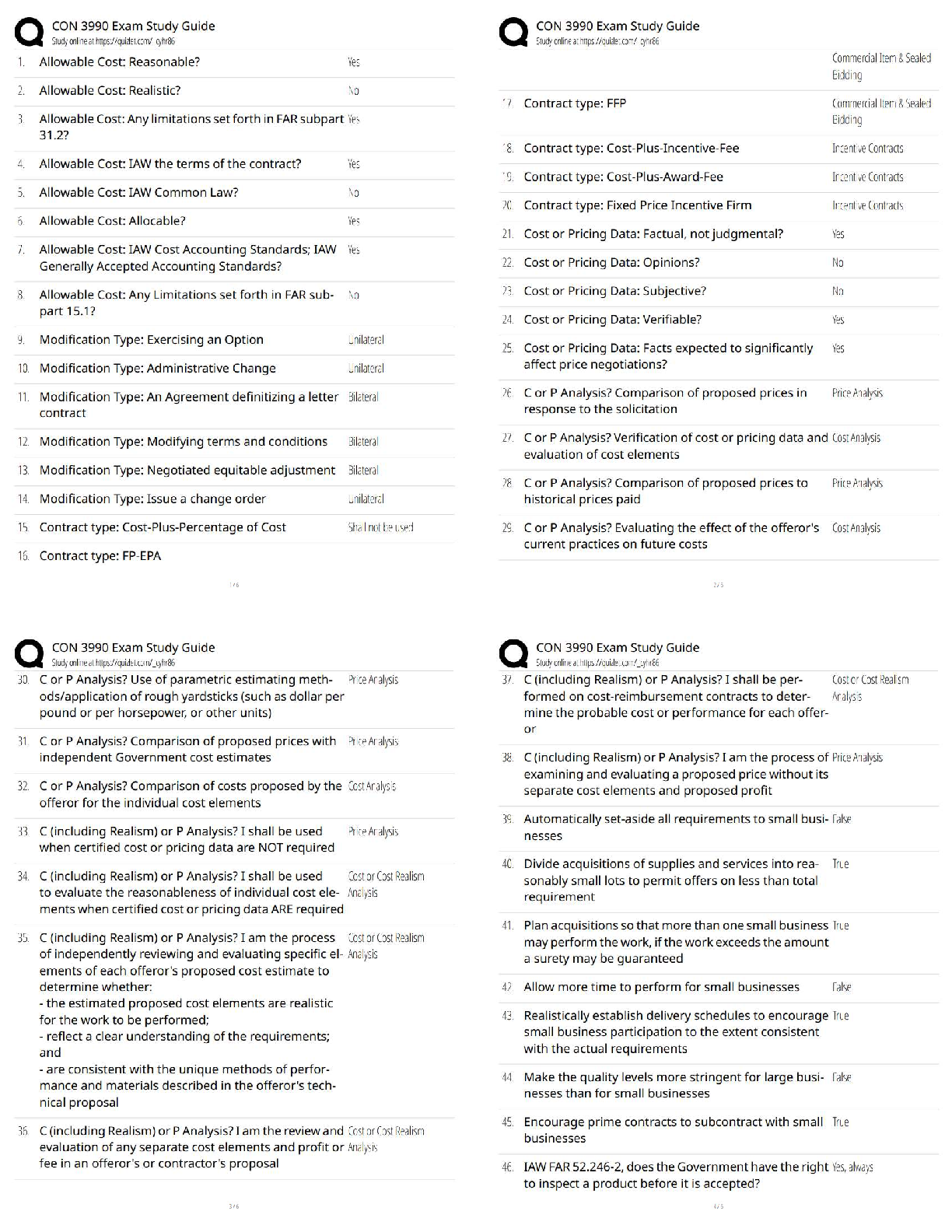

velocities in the horizontal and vertical directions. The figure below explains how.Fig 1. Velocity components and the trajectory of a projectile

Fig. 1 shows a red ball being launched with an initial or starting velocity of v0 meters per

second at an angle of measured from the horizontal. This initial velocity can be broken

down using trigonometry into its horizontal component (v0cos ) and its vertical

component (v0sin). After finding the vertical and horizontal components, different

kinematic equations can used to accurately predict the projectile’s path or trajectory.

If air resistance is small enough to be ignored (generally the case for a small, heavy

ball), then the velocity in the horizontal direction does not change and it is calculated

using the equation:

Horizontal velocity = v0x = v0cos [Equation 2].

Since the horizontal velocity is constant, we can write another useful equation involving

velocity, distance traveled in the given direction (which is the displacement), and time:

Horizontal velocity=v0cosθ=Distance

time

[ Equation3]

On the other hand, for motion in the vertical direction, we can derive a useful equation

by rearranging equation [1] and substituting v0y = v0sin (from Fig. 1) to get:

Launcher v0cos

v0sin v0

Range

Maximum height

Parabolic trajectory

Initial heightv

(¿¿0 sinθ )t−1

2

g t2[ Equation 4]

−h=¿

Here the “-h” is the change in height of the projectile (the height of the floor, which is

zero meters, minus the initial height, which is h meters).

Let us look at an example to see how these equations come in handy:

Example 1: A projectile is fired at an angle of 0 with an initial velocity of 3 m/s. It is

launched from a height of 1 meter above the floor. How far will it travel?

Solution:

We are given the following information:

= 0

v0 = 3 m/s

h = 1 m

We are asked to find the distance traveled (or the range) in meters.

We could use equation [3] to find the range, but we do not know the time the projectile

takes to hit the floor.

Therefore, we will first have to find the time using equation [4] and then use that time in

equation 3. The time the projectile takes to travel the vertical distance to the floor is the

same as it takes to travel the horizontal distance before hitting the floor.

Equation 4 is:

v

(¿¿0 sinθ )t−1

2

g t2[ Equation 4]

−h=¿

substituting the given values and using g = 9.8 m/s2, we get:

-1 = (3)(sin0)t – ½(9.8)(t2)

The sine of 0 is 0, therefore the whole sin term goes away, leaving us with:

-1 = - ½(9.8)(t2)

Rearranging this to get t2 on one side we get:

t2 = 2/9.8Taking the square root on both sides we get:

t = sq.root(0.2041)

t = 0.45 seconds.

Now that we have the time, we can substitute it into equation [3] to find the distance:

v

0 cosθ= Distance

time

[Equation3]

Substituting values we get:

(3)(cos0)= Distance

0.45

The cosine of 0 is 1. Therefore we get:

3= Distance

0.45

which gives us:

Distance=(3)(0.45)

Distance=1.35 m

The projectile will travel a distance of 1.35 meters in the horizontal direction before it

hits the floor.

We could also say that the range of the projectile is 1.35 meters.

Videos:

Please watch these short videos for a review:

https://mediaplayer.pearsoncmg.com/assets/free_fall

https://mediaplayer.pearsoncmg.com/assets/velocity_projectile

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GiiWsXtt5GE

Purpose:

To investigate how the angle of launch and air resistance affect the motion of a

projectile.

Lab Procedure:

Part 1: Changing the angle, in the absence of air resistanceIn this experiment, we will see how the angle of launch affects the distance traveled by

a projectile.

1. We will use the free simulations provided by the University of Colorado, Boulder.

You will need Adobe Flash Player and Java installed on your computer.

2. Open the “Projectile Motion” simulation by Ctrl+ clicking on the link below or copypasting it into y

[Show More]