TutorialTutorial 7 content

2

Reflective writing workshop

Assessments 2 & 3What is reflective thinking?

Reflecting is like observing, remembering and re-running your own actions after something has

occurred. It is yo

...

TutorialTutorial 7 content

2

Reflective writing workshop

Assessments 2 & 3What is reflective thinking?

Reflecting is like observing, remembering and re-running your own actions after something has

occurred. It is your personal response to something which may include:

• why it happened

• how it happened

• whether it was successful or not

• how you might do it differently in the future or what you learnt from it

Why reflect? It is helpful to:

• analyse your learning experiences to make meaning from them, to learn from ‘mistakes’ and to identify what you

still need to know

• make links between theory and practice

• integrate new knowledge with prior learning

• understand how your personal beliefs, attitudes and assumptions underpin your responses to situations

3The basis of your thinking

You need to think not only about what happened in the given situation but also:

• What are your personal beliefs, values, attitudes and assumptions?

• How do these shape your response to the situation?

• Based on these responses, what were you expecting to happen?

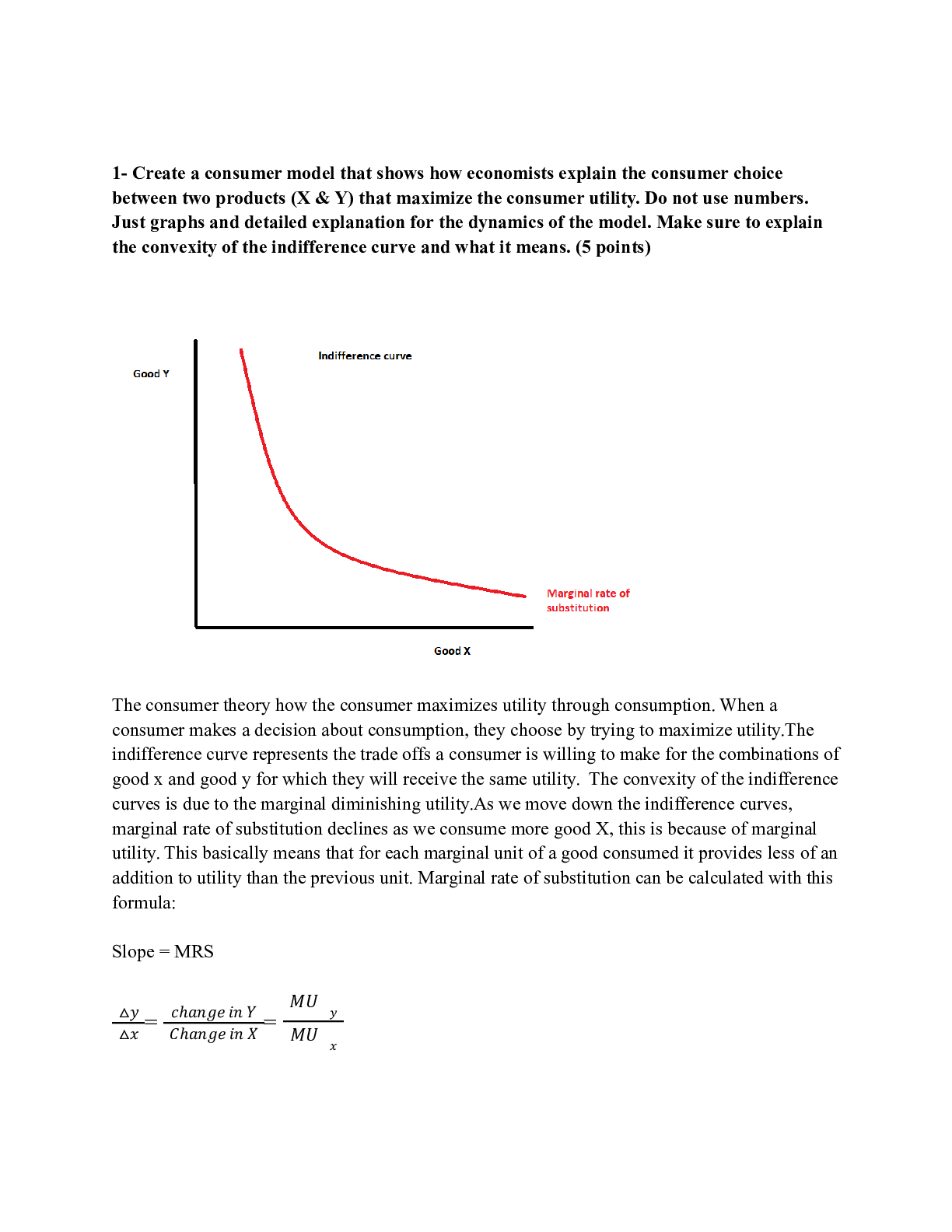

4How to approach a reflective assignment

It can be quite a challenge to think reflectively and even more of a challenge to write

reflectively. The first step is to think about what happened in the given situation. Then you

will need to evaluate why things happened as they did and what you learnt from the experience.

5How to complete reflective writing

1. You need to describe what happened, but more importantly, to demonstrate what you have

learned from a particular experience.

2. It is helpful to ask yourself the following relevant questions and record your responses:

• Why did X happen? What did I do in X situation? What were the positive and negative outcomes in

the situation? How might I do things differently next time? What did I expect to happen? What

have I learned and how does this knowledge contribute to my development?

6The language of reflective writing

• The language of reflective writing is somewhat different to standard academic writing. It is

acceptable to use the first person (I, me, my, we) and so on as this makes sense when writing

about your personal experiences.

• The tone of the writing is more informal than academic writing as you are almost ‘having a

conversation with yourself’ when you write. However, avoid being too ‘chatty’.

• Always write in complete sentences in clear language.

• Make sure that you evaluate your experiences and do not just describe them. Use examples

to make your point, refer to the academic literature, and use appropriate discipline

terminology.

7Incorporating research to support your arguments

Assume you have taken part in a role-playing exercise to simulate a board meeting. Afterwards

you are asked to reflect on your experiences.

• Do some research about board meetings (e.g. about the best way to conduct a board meeting

or how to deal with interruptions during a board meeting). You should now compare this

scholarly evidence with your personal experiences in the exercise. If what happened in the

exercise did not match the evidence then you should write why you think the situation played

out differently. Also, include how research helps to inform what you reflect upon.

89

Analysis of a piece of reflective writing

In our team, we experienced great difficulty in the ‘storming’ stage

(Tuckman, 1965). I had expected that everyone would do what was

needed without being asked. However, people wouldn’t turn up for

meetings or wouldn’t do what they were asked to do. In the end, the

team called a meeting and agreed that clear guidelines had to be

written with instructions for each task that was allocated. We found

in the next few weeks that this method reduced the amount of

tension in the group, and we were able to refer to the written

document to check that everyone did what was promised. I have

learned from this experience that in a team situation, it is better to

establish written guidelines for procedures and tasks from the

beginning; if it is left until there are disagreements and tension, it is

very hard to recover the spirit of goodwill in the team.

You can see that the student has referred to research (Tuckman’s

model of team formation, particularly the storming stage) (Tuckman,

1965), and he/she analysed their own experiences, including their

expectations of team work.

There are several sentences of reflection on:

• what the issue was (people would not turn up for

meetings)

• what was done about it (a team meeting was called with

agreement reached on guidelines for the project tasks)

• how the new strategy improved the situation.

The final sentence explains what the student learnt from the

experience and how they would do things better in the future.10

Working in your team, evaluate the following example, particularly identifying these key elements:

• Student’s beliefs about the issue

• Use of research

• Reflections on what happened

• What the student learnt

Activity11

Example

Last week’s lecture presented the idea that science is the most powerful form of evidence. My

position as a student studying both physics and law makes this an important issue for me and one I

was thinking about while watching the ‘The New Inventors’ television program last Tuesday. The

two ‘inventors’ (an odd name considering that, as Smith (2002) says, nobody thinks of things in a

vacuum) were accompanied by marketing representatives. The conversation seemed quite

contrived, but also was funny and enlightening. I realised that the marketing people used a certain

form of evidence to persuade viewers like myself of the value of the inventions. To them, this value

was determined solely by whether something could be bought or sold—in other words, whether

something was ‘marketable’. In contrast, the inventors seemed quite shy and reluctant to use

anything more than technical language, as if this was the only evidence required and no further

explanation was needed. This difference in their behaviours forced me to reflect on the aims of this

course—how communication skills are not generic, but differ according to time and place.12

Analysis of components

Last week’s lecture presented the idea that science is the

most powerful form of evidence. My position as a student

studying both physics and law makes this an important issue

for me and one I was thinking about while watching the ‘The

New Inventors’ television program last Tuesday. The two

‘inventors’ (an odd name considering that, as Smith (2002)

says, nobody thinks of things in a vacuum) were

accompanied by marketing representatives. The

conversation seemed quite contrived, but also was funny

and enlightening. I realised that the marketing people used a

certain form of evidence to persuade viewers like myself of

the value of the inventions. To them, this value was

determined solely by whether something could be bought or

sold—in other words, whether something was ‘marketable’.

In contrast, the inventors seemed quite shy and reluctant to

use anything more than technical language, as if this was the

only evidence required and no further explanation was

needed. This difference in their behaviours forced me to

reflect on the aims of this course—how communication skills

are not generic, but differ according to time and place.

Student’s beliefs about the issue

Use of research

Reflections on what happened

What the student learnt13

Next week

• Tutorial: Negotiation Simulation 3 (Assessed)

• 1st mandatory Group Planning Form needs to be submitted14

References

Tuckman, B. W. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), 384.

Keates, C. (2018, July 18). Tips on how to write a Reflection. Retrieved from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TyTrg37kfpQ&feature=youtu.be

[Show More]

.png)

.png)

.png)